Basically: A generation is introduced to Candyman and learns why you need to keep his name out of your mouth.

Candyman, Can—yeah, see, we are not going to do that. I am not even going to play around and say his name. Obviously, Candyman is just a fictitious supernatural horror film…but there is no need to tempt the Candyman…EVER. The eponymous cult classic returns thanks to Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld, and Nia DaCosta, the latter of which also directed the film. This is a direct sequel to the 1992 horror of the same name and the fourth in the Candyman film series. However, I will never acknowledge Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (1995), Candyman: Day the Dead (1999), or the aborted Candyman vs. Leprechaun.

I am the writings on the wall. I am the sweet smell of blood on the streets. The buzz that echoes in the alleyways. They will say I shed innocent blood. You are far from innocent, but they will say you were; that’s all that matters.

In the first movie, Candyman is an urban legend who resides within the Cabrini–Green Homes, a Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) public housing project on the North Side of Chicago. Enter graduate student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen), focusing on urban legends and folklore, while stirring up nonsense…because “Candyman.” Candyman is the vengeful spirit of a man who was falsely accused, beaten, and eventually murdered by the police. Now when a person says his name five times in a mirror, that spirit appears and kills the summoner by using a hook attached to the bloody stump of his right hand—if they are lucky.

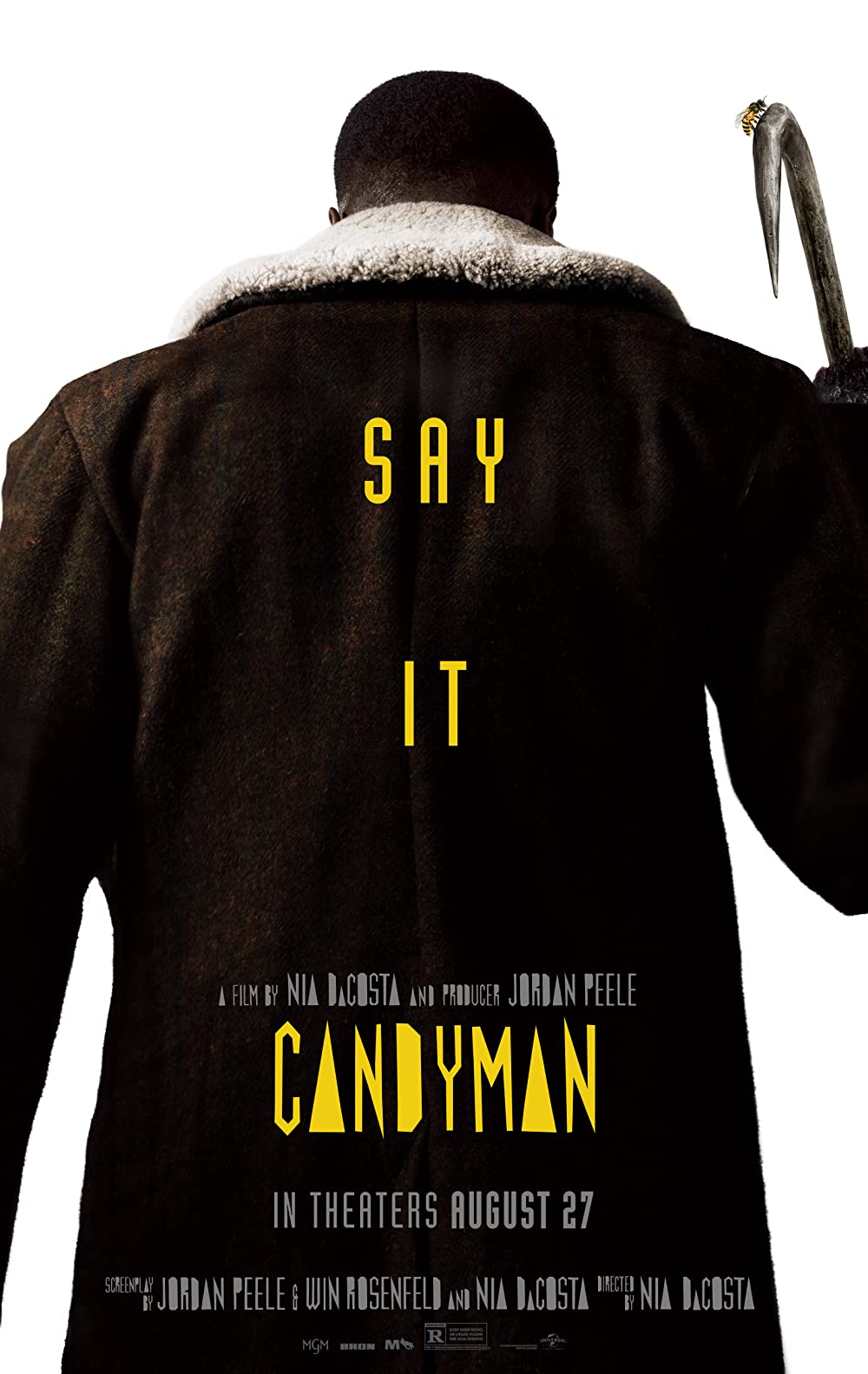

Photo © 2020 Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures

Welcome to now; where we meet Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), a promising visual artist obsessed with the Candyman. As a rising star in the art world, backed by his affluent girlfriend, Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris), the two take on income inequality and gentrification through experimental and daring art—while enjoying the sweetness of Moscato wine. It’s the perfect setup for everything going to hell in a basket.

When the original movie came out, I was 18 years old, and it taught me two things: Keep Candyman’s name out of your mouth (something people in this new movie needed to learn), and Tony Todd is the most terrifying man I have ever witnessed on the screen. The original movie touched on social justice, inequality, and the African-American community’s frustration with the justice system. DaCosta and company decide to go further with the legend. Whereas Candyman (1992) was himself a victim of injustice, today’s Candyman is fleshed out as the vengeful spirit of not just one person but he becomes the embodiment of the trauma resulting from institutional injustice. As a special seasoning, this entry in the franchise is now a reaction to the apathetic awareness of the effects of those traumas, such as class, gentrification, impact on the community, and what harms are done in the name of progress—and the new Jamba Juice joint. As illustrated through one exchange between McCoy and a white art critic who, after the social justice themes are explained to her, dismisses his artistic efforts as “didactic kneejerk clichés about the ambient violence of the gentrification cycle.” Blaming not the displacement of individuals or redlining for the problems of inequality, but instead placing blame on the “artists” who, as she continues, “exploit disenfranchised neighborhoods for cheap rent, so they can dick around in their studio without the burden of a day job.” Yeah, I was really hoping Candyman would visit that critic at some point in the movie.

Photo © 2020 Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures

The first thing of note is DaCosta’s handling of Candyman himself. He is not some rando like Jason Vorhees, Michael Myers, or Freddy Kreuger with mommy and daddy issues or a “sleep” kink. He is a spirit—dark, vengeful, ubiquitous. DaCosta makes his presence constantly known. At times it is direct and blunt, at others it subtly lives on the edge of the senses, terrifying you so much you don’t want to even think about getting a better look. Despite the themes DaCosta puts forward, she remembers this is a horror film, and victims get it in a gruesome, grotesque manner that befits the bloody, crunch-filled karmic retribution they deserve.

Abdul-Mateen II’s portrayal of Anthony McCoy is both critical and heartbreaking. An immediate throwback to the tortured spirit of Basquiat, who also addressed these themes in his art. Anthony’s own explorations of the Candyman are a deep dive into not just the decline of a man but the decline of a community. Leading to a question of his place within the community he seeks to uplift.

Photo © 2020 Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures

Cabrini–Green is shown as a wilted flower in the shadow of the city’s gentrification plans to get the “right” sort into the neighborhood. This is paralleled by McCoy’s affluent girlfriend, Brianna Cartwright, who herself seeks to spotlight injustices from the perspective of noblesse oblige—the obligation of the nobles or in this case the responsibility of Black excellence to uplift the community, not to withhold that excellence because of Black elitism. The portrayal of both paths mirrors the constant tug of war marginalized communities face as they strive to achieve a balance of identity. At the very center of this struggle is Candyman—reminding us of history, a legacy, and that the past remains prologue.

Beginning with panoramic views of the new Chicago vs. old Chicago, followed up with the influx of well-meaning colonizers, explaining what Chicago needs to improve and move on. DaCosta is a bit heavy-handed with themes of class, gentrification, and inequity. At times, so repetitive it borders on monotonous. However, in a world that believes we are “post-racial” and “institutional racism” is a myth like Candyman. I certainly understand the need to flash a brilliant and blinding light on those issues. She wanted to make a point of, what Candyman says in the movie, “Tell Them Everything.”

In the End: Who is Candyman; We are Candyman.