Actually: 8.5

Basically: It’s Almódovar’s mirror and that makes for a fascinating

self-portrait.

I am a fan of Pedro Almódovar’s work. It began when my good friend, Adriana, took me to see All About My Mother in 1999. There was such truth in the quirky mania of the characters, and such sorrow in their dealings with mommy-issues. I was hooked. From there my adoration reached back to Women of the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and forward to films like Bad Education.

Almódovar delights in our weirdness and our everyday hurts, while showing us how wondrous they can be. All these things are more true and more solemn in Pain and Glory than I have ever seen them. Perhaps because this film is the most straightforward representation of the writer/director himself. And so my heart

was captured.

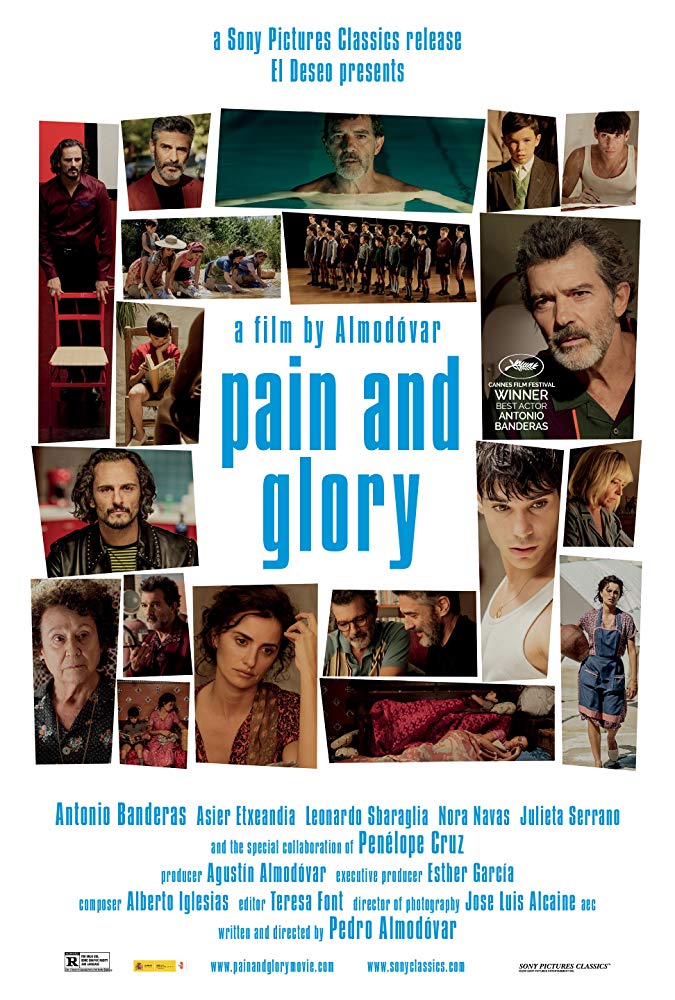

Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Almódovar’s muse Antonio Banderas plays director Salvador Mallo, a much loved artist who is enigmatic enough to meet the requisite for being called an auteur. What his fans don’t know is Salvo suffers from endless pain due to a fused spine and several chronic illnesses. Banderas is stunning in the way he carries his body; back tight, a slight twitch in the cheek, movements slowly deliberate. This physicality gives weight to Salvo as he ventures back out into the world, seeking to celebrate the anniversary of his most lauded film. A hit called Sabor. Ah, but in order to do that he must reconcile with his former star, Alberto Crespo, portrayed with rockstar aplomb by Asier Etxeandia.

We don’t know what caused the riff between the two but we know they’re both still angry. Their words for each other are acid on their tongues. Which turns watching them, as they circle one another, into a wicked glee. But, beneath it all, there is also a love that their dislike can’t quite diffuse. These are such good moments of tension and expectation. There are drugs involved but—rather than be about addiction—Almódovar gives us heroin as a kind of substitute for peyote. The drug is used as a trigger for a spiritual reckoning but also an awakening in Salvo’s life. (Do not try this at home).

From there we are frequently pulled back into Salvo’s younger days, where we meet his mother Jacinta (Penélope Cruz—another of Almodvar’s muses). Cruz is so grounded in her portrayal of a mother who might’ve been too big and too savvy for a sensitive boy to handle. Jacinta is not easy but she is good and because of that you adore the relentless way she pursues life.

Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Where Pain and Glory takes us next is on the journey of an artist rediscovering themselves by reliving and then working to somehow make peace with their mistakes. It is gorgeous. Blues and reds and patterns and textures interplay on screen in the manner of dreams. Almódovar’s surrealist style is more subdued in the storytelling but pops in the settings and also in the way a one-man-play is blocked at the center of the film.

The actors are equally gorgeous; not physically but in the way they move, in the pain they hold in check just out of reach, and in the boldness of their honesty. We are reminded of why we became fascinated with Banderas. He trades sex appeal for a pathos that is solid and endearing—all the more so because it is paired with Almódovar’s favorite trope of bad behavior.

It is a lovely film. The only drawback is that the only speaking role for any black person is that of a drug dealer amongst a gang of black drug dealers. On this point, I must ask Almódovar to do better. Other than that I would like more films with the grace and truth of Pain and Glory.

That is all.

In the End: See it. ‘Pain and Glory’ is a lovely film by a brilliant filmmaker (but don’t do drugs).