Basically: Both grief and identity are very personal things and no one tells Marina how or who to be.

A Fantastic Woman has a deceptively simple logline: A woman loses her lover during a medical emergency, but before she can grieve she’s attacked by his family, who blame her for his death. It’s a classic set up. What sets this film apart is our leading lady, Marina, is transgender. Our perspective changes through Marina’s eyes. She is scorned during the most mundane moments of her daily life—waiting tables, walking down the street, sharing a meal with the man she loves.

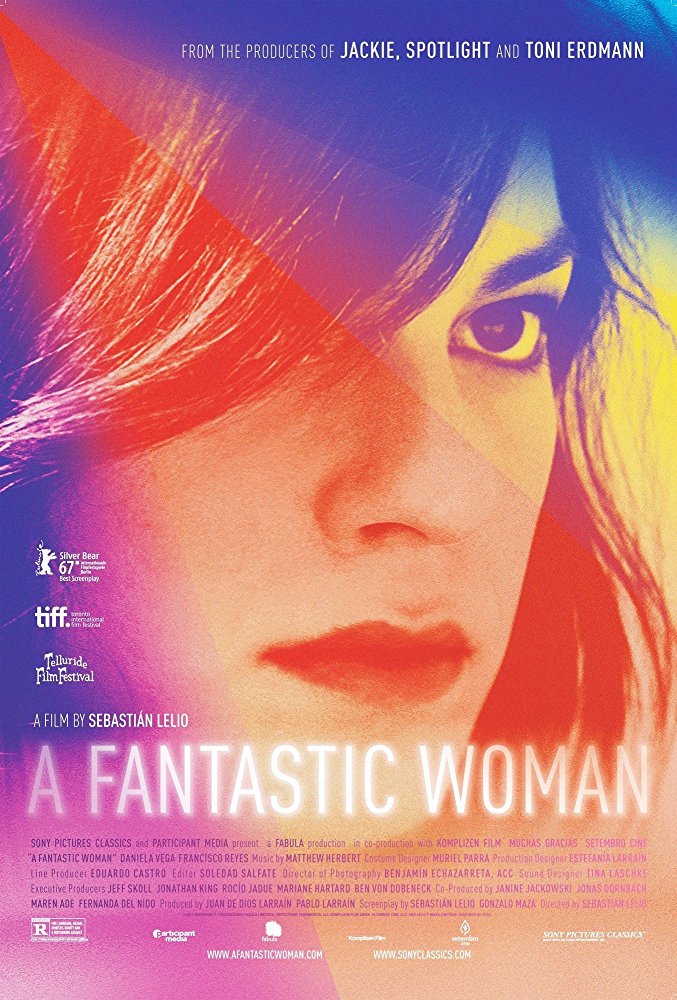

Photo: Sony Pictures Classics

These contrasts are deftly illustrated by director Sebastián Lelio. At the start of the film, Marina (Daniela Vega) seems free to simply be. She leaves work to sing at a nightclub, where she’s a sassy attraction, and her boyfriend Orlando (Francisco Reyes) smiles with such pride when he watches her perform. The pair dance in oblivion at the club, then celebrate her birthday at a Chinese restaurant where it’s clear they are regulars. The sex between them is passionate and just a little naughty as he presses her against their floor-to-ceiling windows. This could be any one of us, but in the middle of the night there is a turning point. Marina drives Orlando to the hospital. He dies. This is when Lelio rips off our rose colored glasses and reveals that normalcy, even during the universal act of grieving, is often a fight for transgender people.

Orlando’s family—an ex-wife, son, and others—have no compassion for Marina. They see her as aberrant and therefore undeserving of their respect. They abuse her verbally and physically; the act of criminalizing and dehumanizing her leaves no room for guilt when they take her home or steal her dog (and we all know stealing a woman’s dog is an act of war). Yet there is something they cannot take: Marina is the one Orlando loved and A Fantastic Woman is a reaffirmation of Marina’s unapologetic womanhood.

Photo: Sony Pictures Classics

There is a steady simmer in Vega’s eyes throughout A Fantastic Woman, the tension in her portrayal of Marina is so intense that when the character finally boils over it is a release worthy of a quiet cheer. We feel for this woman because we want her to have the respect she deserves. As a counterpoint, Orlando’s son Bruno (Nicolás Saavedra) gives us every reason to despise him as he stands in for society’s cruelty in judging those who refuse to conform. And Reyes does incredible work with facial expression and body language, giving us an Orlando who says very little but is very clear in love and in trauma.

Some will be tempted to compare Lelio’s filmmaking to Almodóvar—and certainly their themes are similar—but Lelio tells quieter, more circumspect stories. Both directors make the lives of society’s “others” palpable, but Lelio’s fantastical scenes (like when Marina envisions herself in glitzy musical numbers) play out more like real life daydreams than the surreality Almodóvar employs. Both are wonderful.

In the end: See A Fantastic Woman and cheer when love—of others and of ourselves—wins the day.