I’m sitting down to write this column on Martin Luther King Day, and we’re fast approaching Black History Month. It also just so happens that I finally got around to watching Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis movie the day before. In that, we get to see Presley’s shocked reaction to Dr. King’s assassination on screen. And this is also the week that Lisa Marie Presley tragically died of a heart attack at the way-too-young age of 54.

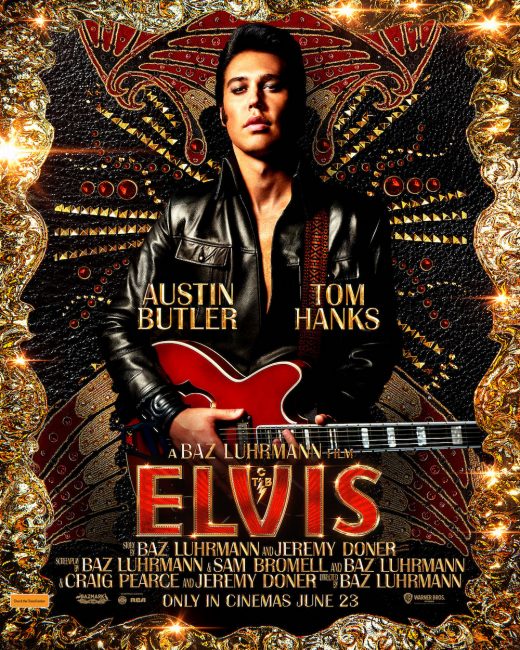

The response to that movie has been mixed, although leading man Austin Butler just deservedly took home a Golden Globe for his performance. Hardcore Elvis fans, of which there are many, have pointed out the historical inaccuracies, though most of those can be explained away with Luhrmann’s cinematic style and proclivity for high drama. Anyone who has seen his Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge! has an intimate knowledge of his style — the story is more important than the minute details of the source material even if, as in this case, the source material is a real life that was lived. The important thing to him is that the spirit is intact.

(If you want to see a fairly extensive fact check of the Elvis movie, The Wrap did a great job.)

—

It’s interesting to think about Dr. King and Presley in parallel today, as two of the most iconic Americans to have lived — for different reasons. While adored in many quarters, Presley has also been a controversial figure. He’s been accused of racism, and/or of benefiting from systemic racism.

While the latter is undoubtedly true (because he was a white man in America, of course, it’s true), there’s actually no evidence of the former.

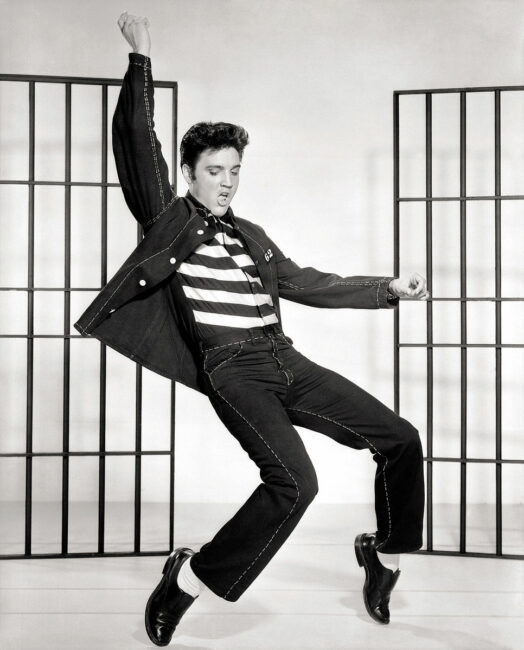

One of the things that the film basically gets right is that Presley’s mom was very poor and he spent his early years in one of the houses designated for white people in a Black area. It’s often said that Presley played his part in the formative years of rock & roll by blending the blues and country and popularizing it by capturing both audiences. That’s obviously a simplification, but it is true that Presley was enthralled by the blues, and blues musicians, from an early age. The dramatized version of that in the film is when we see child-Elvis getting his little mind blown by a couple dancing raunchily to the blues, one minute, and then to enthusiastic gospel music in the church the next — which is one of the movie’s great scenes.

That was the world that Presley grew up in, and he didn’t let anyone forget it. It’s true that, when somebody called him the King of Rock & Roll early on, he pointed out that Fats Domino is the true King.

Now, of course, none of this alone is proof that Presley wasn’t racist. The “I’ve got Black friends” argument is cringy, to say the least. But the key is there’s no evidence that Elvis was racist.

There has been a rumor going around for decades that Presley said, “The only thing a Black woman can do for me is buy my records and shine my shoes” (or a variation of that, switching “women” for “man” or even the “N” word). David Pilgrim of the Jim Crow Museum cleared this up in 2006 when he wrote, “Many Whites in the 1950s, including celebrities, had used anti-Black rhetoric. It was easy to believe that Presley, the Mississippi-born, once-working class, former truck driver had ungratefully lambasted Blacks. There is no evidence that it happened. Moreover, there is evidence that Presley donated money to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other civil rights organizations; he publicly lauded Black musicians; and, treated the Blacks he encountered with respect.”

For his own part, Presley told Louie Robinson, a reporter for Jet magazine in 1957, “I never said anything like that, and people who know me know I wouldn’t have said it.”

Robinson, a pioneering Black reporter who died in 2015 at the age of 88, concluded, “To Elvis people are people, regardless of race, color or creed.”

That said, Elvis absolutely benefited from systemic racism. How could he not? The movie captures this at the start when Colonel Tom Parker agrees to include Elvis on his Hayride tour because the man singing Black music is indeed white.

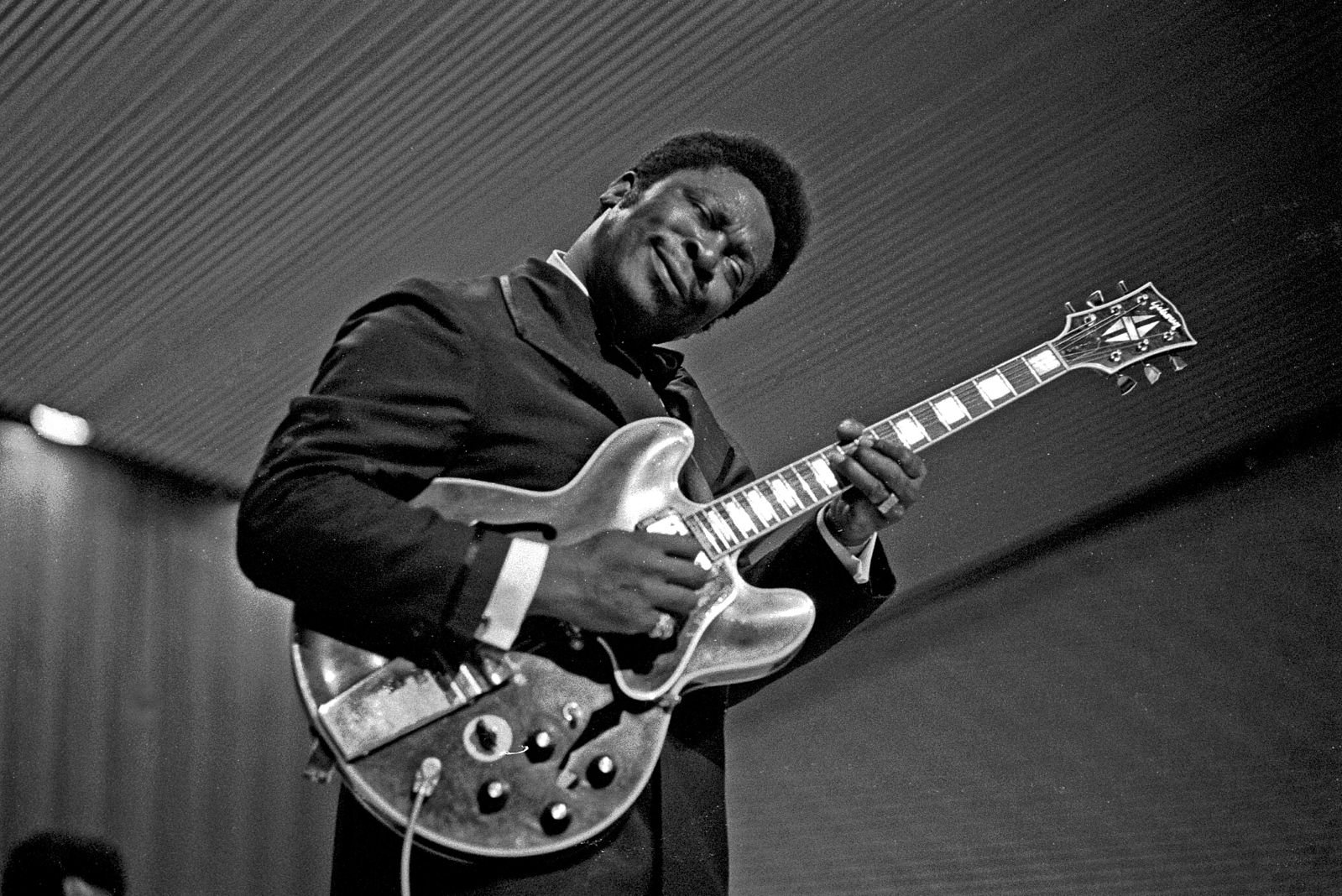

Had Elvis been Black, he wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. Although, the idea that he simply stole music is a bit of a fallacy too. As B.B. King wrote in his biography, “Elvis didn’t steal any music from anyone. He just had his own interpretation of the music he’d grown up on, same is true for everyone. I think Elvis had integrity.”

—

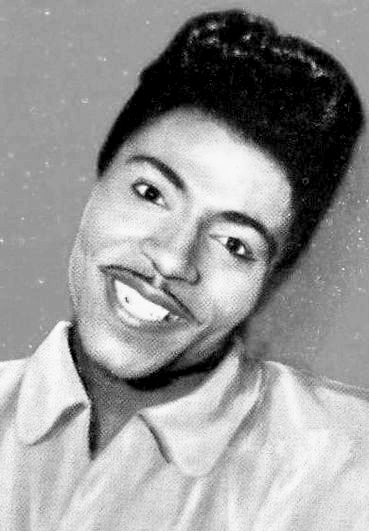

Fellow pioneering rocker Little Richard said of Elvis after his death, “I love him. That’s my buddy, my baby. Elvis is one of the greatest performers who ever lived in this world. [But] if Elvis had been Black, he wouldn’t have been as big as he was. If I was white, do you know how huge I’d be? If I was white, I’d be able to sit on top of the White House! A lot of things they would do for Elvis and Pat Boone, they wouldn’t do for me.”

That isn’t even debatable. Elvis was able to achieve a level of success that Black performers couldn’t, simply because of the color of his skin. It’s true that he hired Black musicians and backing singers, that he helped people whenever he could, and that the vast majority of people who came in contact with him, with the notable exception of Quincy Jones (who called Presley a “racist mother…” in an interview but wouldn’t elaborate), say that he treated everyone with respect.

Like most things, the conversation is nuanced. And Elvis isn’t around to speak for himself. Maybe he’s with his daughter now.