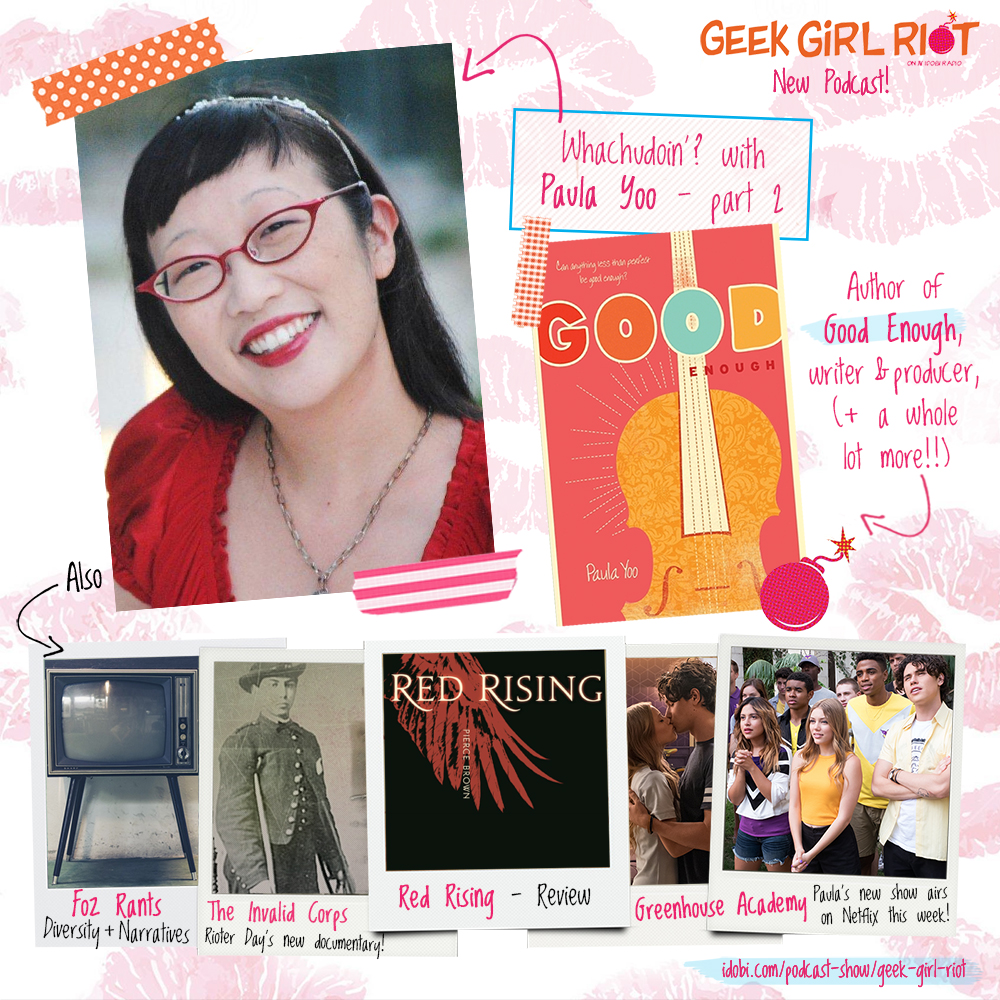

The lovely Paula Yoo is back on Geek Girl Riot this week for round 2 of her Whachudoin’? special. That’s right, the writer/producer/picture book creator/actual superhero has packed so much into her life we needed to split her Whachudoin’? into two parts to cover everything. Catch up on part 1 if you missed it here, then hit play below to check back in with Paula as she chats with Sherin and Day about her YA novel Good Enough (reading list below), being a classically trained violinist, and trying her hand at a little bit of everything. Be sure to look out for Paula’s new show Greenhouse Academy, which premieres on Netflix this week!

Once we leave the wonderful combo platter-filled world (her words, not ours) of Paula Yoo, we head to Mars for Renee’s book review of Red Rising by Pierce Brown. The 2014 sci-fi novel follows the life of Darrow, a miner and a Red—the lowest caste in the future’s color-coded society—who spends his life digging so he can make the surface of the planet habitable for the next generation…until he discovers his life’s work isn’t quite what it seems.

Sending off the show with a bang is Foz Meadows, who joins us for one of her iconic Foz Rants, because yelling is self-care. This time she takes on the issue of diversity and narrative, and damn, does she get into it—join her, won’t you?

We’re so very proud of our friend and fellow Rioter Day Al-Mohamed for putting out her own documentary, The Invalid Corps, which tells the stories of the men who had been “disabled by wounds or by disease contracted in the line of duty”, who served as guards, escorted prisoners of war, provided railroad security, and performed a vital service and honorable duty to their country. “This is the story of men with disabilities, of men with honor, and of men whose place in history shouldn’t be forgotten.” You can find out more about the documentary here.

If you haven’t heard, Geek Girl Riot is now on idobi Radio! Tune in every Tuesday at midnight (aka Wednesday morning) for your dose of late-night geekery from our team of rioters. For now, see below for a list of Paula’s books (which we highly recommend you pick up right away), and a transcript of Foz’s latest Rant.

READING LIST: PAULA YOO

– Want to Play? – Book #2 of the Confetti Kids series

– Lily’s New Home – Book #1 of the Confetti Kids series

– Twenty-Two Cents: Muhammad Yunus and the Village Bank

– Shining Star: The Anna May Wong Story

– Sixteen Years in Sixteen Seconds – The Sammy Lee Story

—

Foz Rants – Transcript

Hello, and welcome again to Foz Rants, where yelling is self-care.

The thing is, I’m so fucking angry right now about so many things that I hardly know where to start yelling.

For one thing,

You’ve had worried parents arguing for the better part of fifty years that seeing certain violent or traumatic acts on TV can be damaging to children, but far too many of those same fucking people – probably the conservative subset that got up in arms about DND as a gateway to Satanism – can’t admit that kids not seeing certain things is damaging, too. A failure of diversity, the inability of children to see themselves or people like them portrayed with humanity, accuracy and consistency, can do worse and more lasting harm than any one glimpse of age-inappropriate gunfire. But of course, of course – the rule is that you can’t prove a negative. You can’t prove that the absence of a thing is damaging, only that its presence is – except that, yes, in this particular instance, you can: A, by looking at the before and after of kids shown for the first time that they exist in stories, and B, by talking to now-grown adults about how awful it was to feel so goddamn invisible in childhood.

So let’s get this shit on the record: socially, you can prove a fucking negative. You can prove that taking a thing away, or refusing ever to offer it in the first place, has consequences. We know damn well that denying healthcare to the poor is a bad idea, and you can chase that particular precedent back to the goddamn time of plagues. We know very well what happens when you give large swathes of the population little or no education, too, and the only reason we’re having to remind people about the consequences is because they’re already starting to happen.

See, the thing about stories is that they’re not all created equal, and the thing about history – or rather, about the way it’s most commonly taught and transmitted – is that it’s a story, too. And so much of what’s happening in the world right now is so bizarre, so unprecedented in the modern era, that there’s an inherent temptation to view it as a hyped-up fiction: after all, it’s frequently presented as one through news articles and broadcasts and Facebook posts. In stories, the macro of events is always intangible to their participants: as a reader, you invariably know more about what’s going on than the characters, because you can see the overarching plot in a way they can’t. The problem we’re having now, in real life, is that the media is reporting on so much macro – so many things that feel like a major plot convergence for the whole damn world – that, unless you’re caught in the middle of things, it doesn’t feel any different to a story. A part of our brain thinks, oh yeah, I’ve seen that movie, and takes a perverse reassurance in the familiarity of this live-action drama about corrupt, selfish, cartoonish, incompetent politicians and the threat of the end of the world.

We’ve told stories about exactly this sort of scenario playing out for decades now, and instead of making us collectively vigilant against it ever coming true, we’ve quietly assumed that it must actually be impossible, because that’s what happens when you trick yourself into thinking that the how and why of stories doesn’t matter; that they’re all made up, and that’s all there is to it. Like the apocryphal tale of the man who habitually carried a bomb in his luggage when flying as a preventative against his plane getting blown up, because – he believed – it was astronomically implausible for there to ever be two bombs on the one flight, we’ve maintained a culture of storytelling about the devastating potential consequences of ignorance, apathy and cruelty in a way that has simultaneously served to make us ignorant, apathetic and cruel, not because we’ve always told bad stories, but because we’ve persisted in our belief that, unless they’re being told to children, they don’t matter; and even then, that all that matters is what’s shown, and not what’s omitted. All those times that hypothetical, fearful man brought a bomb on his plane, he risked it going off by accident, because the plain fact is, a preventative measure that looks and acts identically to the threat itself is no prevention at all, but is rather the exact same threat with a secretly randomised trigger.

Why does the hypothetical man take a bomb on a plane? Because he’s scared of bombs. Because he’s afraid, he leans into doing exactly the thing he’s frightened of, mistakenly assuming that, because it’s his choice, he’s in charge of the consequences. But that’s not how randomised triggers work: you fly with a bomb in your bag often enough, and sooner or later, it’s going to explode.

Ironically, this particular urban legend has now been rendered anachronistic by history. As I recall, it’s something I first heard as a kid, before the events of September 11, 2001 made the idea of anyone casually smuggling a bomb onto a plane seem both morbid and grossly implausible, to say nothing of being a particularly tacky joke. But even if my memory’s wrong and it is a post-9/11 myth, born in that awful period of fear and black humour, it still doesn’t feel quite the same to us now. See how stories change with the times? One year, a plane blowing up is a narrative device so far-fetched, it could only happen in Hollywood; the next, it’s a trope deployed with pinpoint accuracy to evoke a specific type of fear, a specific type of patriotism. We know what it means to tell that sort of story now – but then, we thought we knew what it meant before, too. What stories mean is subject to change depending on their context, but they always matter – just not always in the same ways, or to the same people. They’re like the weather, in that respect, which is why it’s not inaccurate to use them as a sort of cultural barometer. We expect meteorologists and forecasters to keep us informed in hurricane season, but when storytellers start saying, as they did several years ago, that there’s been a frightening shift in the social climate – rape threats and Puppies and GamerGaters, oh my! – we seldom accord them the same expertise in their field.

Incidentally, it’s now hurricane season in the United States, and both NOAA and FEMA are leaderless under the Trump administration. How’s that for narrative irony?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download