Just as sound bites get reworked into tunes that multiply over the Internet – Remember all the songs based on Howard Dean’s yelp? – a widely seen TV ad is getting the hack-and-slash treatment.

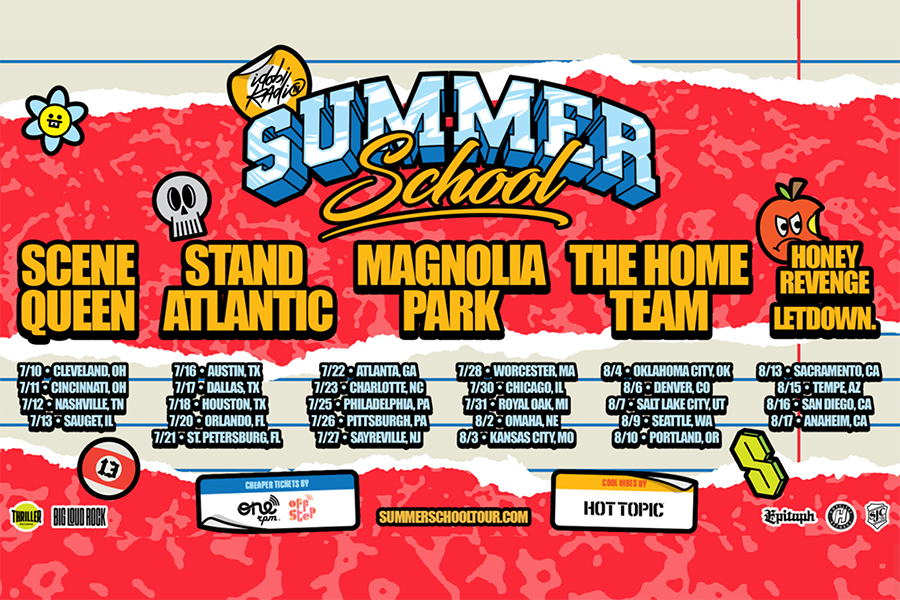

The target is Pepsi’s current promotion giving away 100 million free song downloads from Apple’s iTunes Music Store. The company promises one in three bottlecaps on certain Pepsi products carries a code for a free iTunes download.

Pepsi is airing a 45-second spot featuring 16 crestfallen music downloaders who have been sued by – and settled lawsuits with – the record industry for illegally snagging songs online. It ends with one of them, a young girl raising a Pepsi and defiantly declaring, “We’re still going to download music free off of the Internet,” but she is referring to songs acquired from iTunes thanks to lucky Pepsi bottlecaps.

While some praise the commercial as a cheeky dig at the litigious Recording Industry Association of America, Brian Flemming fumed when he saw it.

Flemming contends that by promoting the concept of RIAA-approved downloading, Apple has turned 180 degrees away from its core philosophy – the one expressed 20 years ago in the trailblazing “1984” ad in which Apple hammered groupthink.

“I hate it when Apple makes me hate Apple,” the Mac lover wrote on his Web journal. “This ad is just…. Words fail me.”

So, the Los Angeles independent filmmaker sat down at his computer, a Mac, and made a video remix of the Pepsi commercial that adds his own text: “Fear is a primary means used by The Party to maintain control over expression in ‘1984.’ Fear also is a potent weapon used by the RIAA to exert control over the behavior of music fans.”

The buzz grows

Halfway across the country, graduate student James Saldana at Southern Illinois University was sitting at his computer, a Mac, putting the finishing touches on his own take of the ad. His text: “The recording industry cheats artists, screws consumers. Who is the real criminal?”

Independent of each other, the men posted their video remixes and watched incredulously as the buzz grew.

Parodies of magazine ads are nearly as old as the Web.

Users of Photoshop and other digital imaging programs in the mid-1990s altered images and posted them for friends. In the late ’90s, college students used campuses’ fast Internet connections and server space to host a scattering of ad parodies, such as a funny bit that had cartoon Superfriends performing the Budweiser “What’s Up?” ad slogan.

Today’s faster computers, the proliferation of faster Internet connections and the widening availability of commercials on the Internet are letting even more pranksters – and people with points of view – easily alter moving images.

The Pepsi ad drew Flemming’s and Saldana’s attention because of its link to the RIAA, and because they knew the ad – first aired during the Super Bowl – would be widely seen.

But neither knew what the Web community’s reaction would be.

“I didn’t expect anything,” Saldana said as he watched one of the school’s servers spit out data at a rate of 1 megabyte per second to computer users viewing the remix. “I’m surprised by the amount of bandwidth going out.”

A bountiful Internet

Video remixers gather video from the Internet, where many companies post their commercials, and spend five to six hours cutting and repasting images and adding text to make a point.

“My college students are seeing spoof ads all the time,” said Rachel Mayeri, who teaches mass communications at Harvey Mudd College in California. “This type of ad parody is typical of students who read through most of the messages that corporations produce in advertising.

“Advertising is an important force to be reckoned with. Ads are so sophisticated these days that they can appear to be anti-advertising and yet they get their brand across and they still wind up being seductive to the youth market.”

Flemming said he created a clip to carry his message because “I get tired of the strident opinion expressed on blogs.” It’s the second time he has remixed an ad; the first, which he created a couple of weeks ago, showed Dean’s post-Iowa caucus pep rally and howl from the perspective of a camcorder held by an audience member.

He juxtaposed those images next to 1992 footage of George W. Bush sipping an unidentifiable liquid at a party. Flemming titled the piece “Who’s More Presidential?”

“It bugged me that the media had misrpresented the moment,” Flemming said, explaining why he created the Dean clip.

After posting that work a couple of weeks ago, the number of his Web site visitors went through the roof, Flemming said. “I got more than 10,000 hits in a couple of days, and that’s more people than had seen [his documentary] ‘Nothing So Strange,’ which has been on the festival circuit for two years.”

“This opened my eyes to the power of the Internet,” he said. “It’s the new broadcasting.”