(Source: Nate Anderson – http://arstechnica.com)

With a new school year in full swing, Ars takes a look at the RIAA’s newly updated copyright curriculum. Your kids could be learning from it–so what does it say?

School kids in America could certainly stand to learn about copyright in the classroom–it’s a fascinating topic that increasingly impacts the life of every “digital native” and intersects with law, history, art, and technology. But should they be exposed to industry-funded materials meant to teach kids:

School kids in America could certainly stand to learn about copyright in the classroom–it’s a fascinating topic that increasingly impacts the life of every “digital native” and intersects with law, history, art, and technology. But should they be exposed to industry-funded materials meant to teach kids:

- That taking music without paying for it (“songlifting”) is illegal and unfair to others (RIAA)

- Why illegally downloading music hurts more people than they think (ASCAP)

- How the DVD-sniffing dogs, Lucky and Flo, help uncover film piracy (MPAA)

- To use problem-solving approaches to investigate and understand film piracy (The Film Foundation)

- The importance of using legal software as well as the meaning of copyright laws and why it’s essential to protect copyrighted works such as software (Business Software Alliance)

If this sounds more like “propaganda” than “education,” that’s probably because Big Content funds such educational initiatives to decrease what it variously refers to in these curricula as “songlifting,” “bootlegging,” and “piracy.”

Music’s rules

The industry loves to talk about the need for “education” (it did so again this morning at an FCC broadband hearing), and it’s proud of the work that it produces. As students start a new school year across the country, the RIAA is talking up its recently updated Music Rules! curriculum, which really does attempt to lay down the Ten Commandments for online activity. (Number 10: “Always show respect for intellectual property”).

We took a look at the updated curriculum, which was developed by “curriculum specialists.” A closer look at the program documents show that Music Rules! was developed by Young Minds Inspired– a group that also wrote the Copyright Alliance’s classroom program and produced one for the Entertainment Software Association. The YMI websites shows that the company’s most recent “free” materials were in support of movies, TV shows, and the NFL (which actually passes out football trading cards to students and includes a helpful guide of football terms for “those with little or no knowledge of the game”).

Like most such efforts, Music Rules! isn’t so much “wrong” as it is “woefully incomplete.” When one of the program’s stated objectives is to teach students that “taking music without paying for it is illegal and unfair to others,” it’s clear that this is not a subtle approach (one wonders how Radiohead, Trent Reznor, Jonathan Coulton, and pretty much every band everywhere who gives away free songs on its website would react to this statement). There’s something to be said for simplification, but this is ridiculous.

Music Rules! starts by defining the terms that teachers need to know about copyright in order to cover the material. The complete list (we kid you not) is: counterfeit recordings, DMCA notice, “Grokster” ruling, legal downloading, online piracy, peer-to-peer file sharing, pirate recordings, songlifting, and US copyright law. That’s it! The fact that “pirate” appears twice while “fair use” is entirely absent pretty much sums up the approach.

At least the curriculum doesn’t pull any punches by pretending to offer anything approaching “copyright education”; it is only about “respecting all forms of intellectual property, especially music recordings.”

But that doesn’t mean schools should be adopting it, free or not. Consider the very first suggested activity, one targeted at students in grades 3-5. It’s about “songlifting,” a term we have never seen before, and it suggests that students calculate how much harm songlifting does to copyright owners. This is “educational” because, as the program notes, students “will be using their math skills to investigate songlifting.” Unfortunately, critical thinking skills will be left at the classroom door.

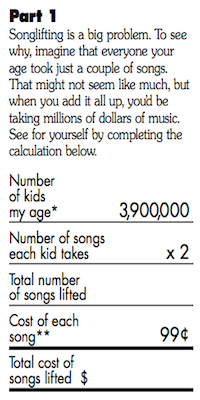

The exercise asks students to “choose a realistic number of songs they would take if they could get them all for free.” With a teacher’s help, students then calculate how “big a problem” songlifting is–by multiplying the total number of songs by $0.99. The included worksheet calculation shows that 7,800,000 songs equate to $7,722,000.

Teaching the factual claim that “sharing full copyrighted files without the rightsholder’s permission is generally illegal” is fine, but this sort of calculation is simply ridiculous. If students in grades 3-5 are downloading songs from P2P networks and the music industry truly believes it’s “losing” $0.99 each time, some “education” is certainly needed, but not necessarily for the students.

The curricula doesn’t show much thought (or updating; it still talks about the Rio, Zen, and Walkman as common portable media players). The first grade 6-8 activity is identical to the one described above… but the calculation is done on a spreadsheet. Genius!

Students are also asked to pretend that they are entering a recording studio; one suggested “rap” they are to sing follows:

Music is worth it, if you’re asking me

True words, new rhythms, sweet melody

Just tell me where to get it and I’ll gladly pay

For a song that says what my heart wants to say.

But don’t try to fool me with aphony [sic] copy,

‘Cause songlifting’s wrong, and it’s got to stop, see?

At the end comes a pledge that students can sign, in which they vow to “respect all forms of intellectual property,” “obey the copyright laws that protect intellectual property,” “always use computer technology responsibly,” “always use Internet technology safely,” “never accept illegal copies of songs online or on disc.”

Corporate-funded education materials have always been controversial, and the Music Rules! program reminds us why that is. Teachers are encouraged to advocate for one specific industry and address one specific concern, rather than broadly talking about copyright. The agenda is obvious; so too is a general lack of interest in fair use, the public domain, Creative Commons, the history of copyright and its absurd post-1976 expansion, students as copyright owners, the repeated “moral panics” over the player piano, home taping, and the VCR, etc, etc.

Still, it could probably be worse.