On Thursday, September 8, Queen Elizabeth II died at her residence of Balmoral Castle in Scotland. She was 96 and reigned for an incredible 70 years.

No doubt, you already knew that. The TV news outlets have been airing stories about the royal departure seemingly on a loop ever since she left this mortal plane of existence. To be fair, it is world news. That there is a new reigning monarch in the UK for the first time in most people’s lives is undoubtedly worth a few cable segments and column inches. It’s also fair to note that she was 96 and lived a life of immense privilege.

Sitting here as a British and American dual citizen, I’m well aware the Crown means different things to different people. If the Queen’s death has opened up fresh dialog about the wrongs committed in the name of the British monarchy in the not-too-distant past, then that can only be a good thing.

It is massively complicated though.

On one hand, it was during the Queen’s reign that the British empire was dissolved—African nations were decolonized—and in its place came the Commonwealth (including Canada) which countries could opt out of should they wish.

On the other hand, the British throne is the very symbol that represents colonization and therefore repression—whoever sat on it. But hey, context never hurts.

The Queen became Queen in February 1952. Five years later, in March 1957, Ghana attained independence. Somalia and the Federal Republic of Nigeria followed in 1960. 1961 saw Sierra Leone, Nigeria (British Cameroon North), Cameroon (British Cameroon South), and Tanzania gain independence. Uganda in ’62, Kenya in ’63, Malawi and Zambia in ’64, The Gambia in ’65, Botswana and Lesotho in ’66, and Mauritius and Swaziland in ’68. There was a gap leading up to Seychelles’ independence in ’76, and finally Zimbabwe in 1980.

So yes, five years into her reign the first country was independent. Sixteen years in, the bulk were independent. Some might say that, after centuries, that rate is only realistic. But for the people living under colonial rule for those five years, or eight years, sixteen, and so on, that’s little consolation.

So some empathy is required when considering the words of Nigerian-born Carnegie Melon University lecturer Uju Anya who, upon learning of the Queen’s declining health, wished her excruciating pain and then bizarrely got into a war of words with Jeff Bezos of all people. She later clarified in a Tweet, “If anyone expects me to express anything but disdain for the monarch who supervised a government that sponsored the genocide that massacred and displaced half my family and the consequences of which those alive today are still trying to overcome, you can keep wishing upon a star.”

Again, it’s complicated. And a reminder that the pain doesn’t necessarily end after independence is granted if that transition is not carefully managed.

Moses Ochonu, a professor of African studies at Vanderbilt University, told NPR, “It’s her dual status as the face of colonialism, but also a symbol of decolonization that defines how she is perceived in many former British African colonies.”

Reports differ on how much the Queen actually wanted independence for those African nations or how much she resisted it. And even that is complicated by the fact that the monarchy has little actual power in government anyway. It’s been little more than a ceremonial position for a long, long time.

Ultimately, feelings and forgiveness belong to individuals and everyone has a right to feel about the queen exactly how they feel.

Progressive folk-punk Billy Bragg is worth listening to. The guy has long been on the side of the working man and posted a thoughtful essay to mark the Queen’s passing:

“Personally, I’ve never had strong feelings about the monarchy and the cosmetic role they play in our constitution,” he wrote. “My concerns have always been about the way the powers which were once the sole preserve of the monarch have been conferred onto the prime minister, allowing the holder of that office to declare war and sign treaties without recourse to parliamentary debate. Hopefully the ascension of Charles III will initiate a debate about the role of the monarchy in a modern democracy, perhaps helping to kick start reforms such as the abolition of the House of Lords and a written constitution.”

“Having said that, I do want to take a moment to reflect on the passing of a person who has played a role in our national life over the past seven decades that is unrivaled in its significance,” he continued. “The importance of the Queen as a figurehead was made clear to me in 2007 when I saw a news report of the dedication of the Armed Forces Memorial, remembering those who lost their lives in conflicts since the Second World War. Watching the Queen walk along a line of ex-service personnel who had fought in every war from Korea to Afghanistan, I was struck by the thought that there is no one in British public life whose presence at an event could be equally meaningful to an 80 year old veteran as well as one in their 20s.”

Bragg concluded with, “So when they bury her next week, I too will mourn – not so much for the passing of a monarch, but for the passing of a generation.”

As a Brit, that’s what this means. The passing of what has been the face of a nation for 70 years. It’s very possible to feel that and also understand the cruelty of colonization.

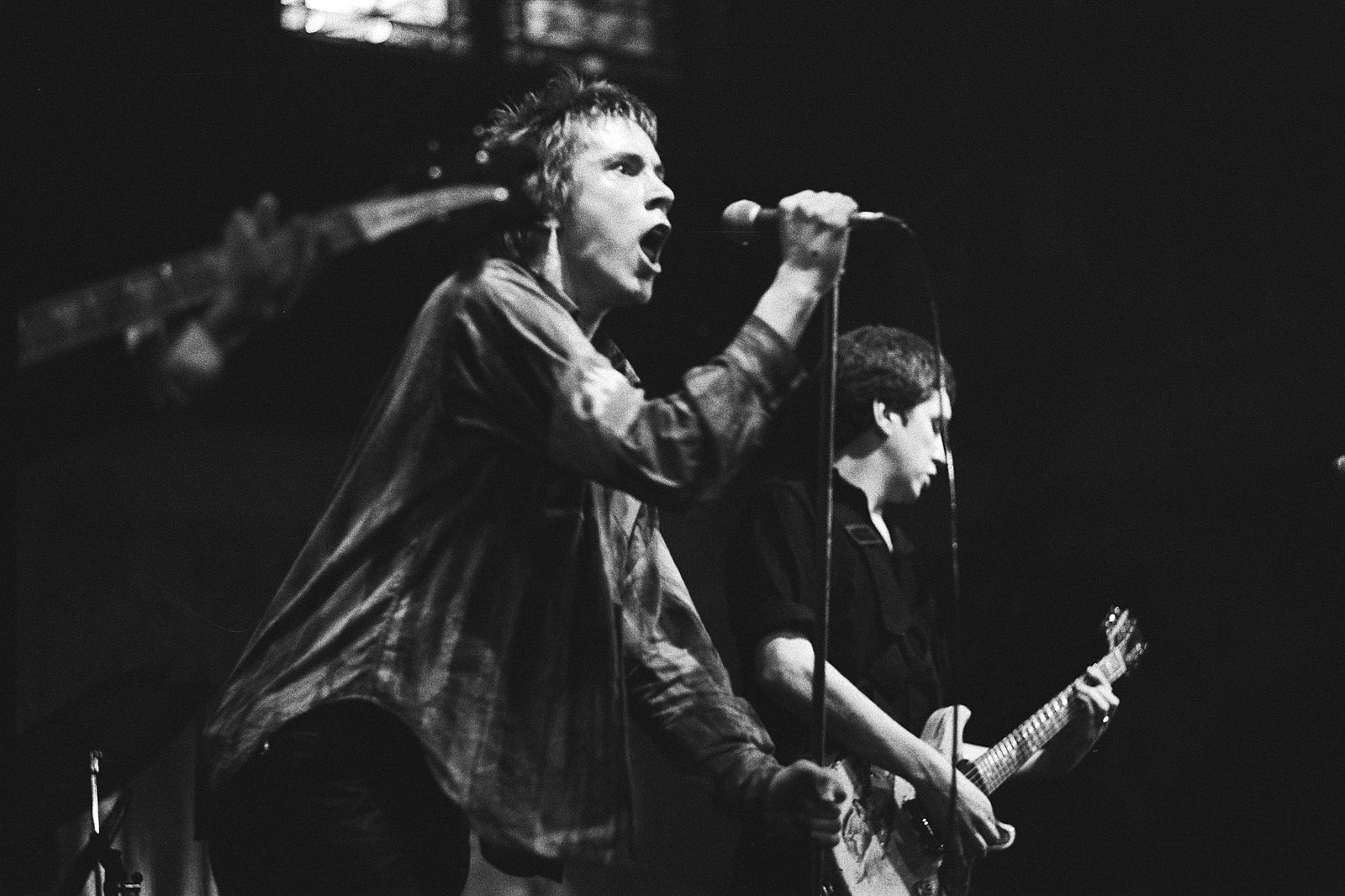

This writer grew up with the words of the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” ringing in the ears—the ultimate anthem of anti-royalist rebellion. When John Lydon marked the Queen’s passing with the words “Send her victorious,” it was a sign that he had softened.

Perhaps he shouldn’t have.