Back in the early 1980s, punk scenes started to develop in California. Los Angeles and San Francisco in particular saw what was going on in New York, Detroit, and England, picked up the baton and ran with it, adding a nihilistic yet sort of goofy twist that was very different to what had come before. Bands like the Germs, Black Flag, X, and the Avengers took what they were doing seriously but appeared to be having more fun than punks from those other cities. And one of the originals, rubbing his hands with glee at what was unfolding before him, was Geza X.

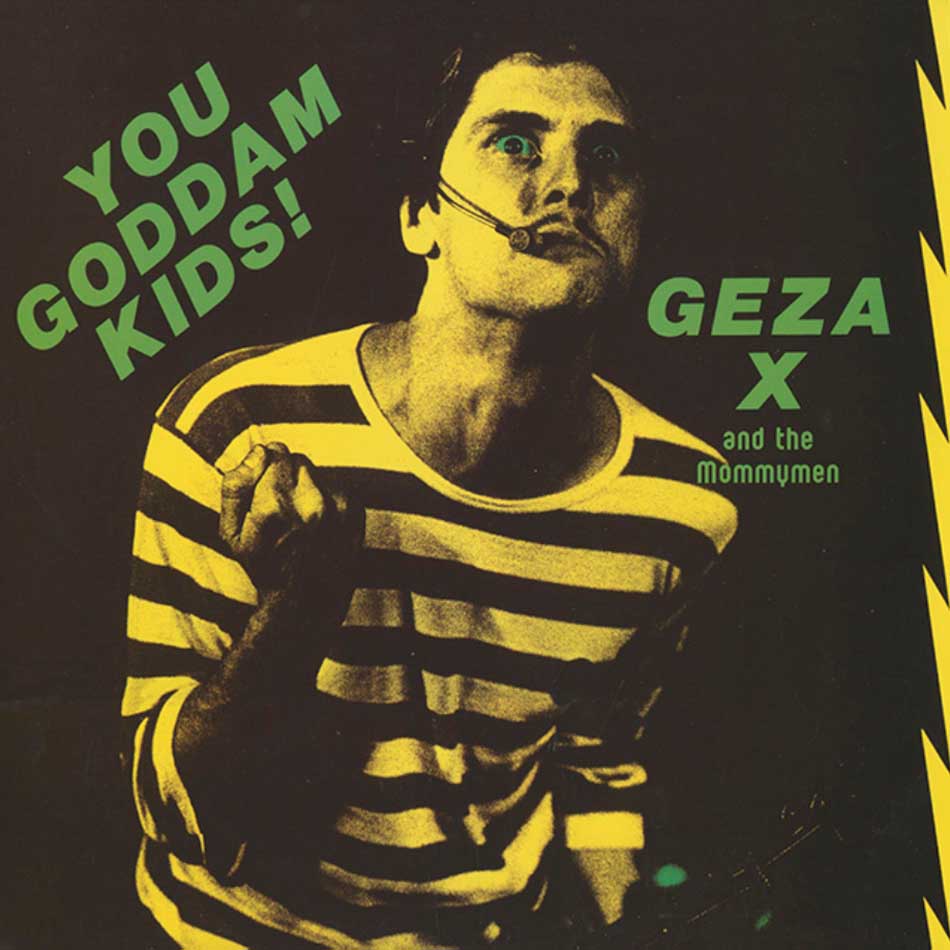

Geza had his own band, the Mommymen, and they put out a beloved but often overlooked album called You Goddam Kids!, plus the “Isotope Soap” single in 1982, but he’s better known for his production credits. Think of an LA punk band from that era, and chances are Geza X produced them at some point, or at least mixed them live. Into the 1990s, he achieved some commercial success when he produced the mega-hit “Bitch” for Meredith Brooks. Nowadays, he’s running the Vortex—a community center, studio and multimedia theater—something that would have seemed like a pipe dream when he started playing around with rudimentary recording devices when he was young.

“When I was a kid, I really fell in love with a tape recorder called the Recordio,” says the man born Geza Gedeon. “I was four, and this thing was a do-everything box. You could cut a record on it, you could use it as a PA system, you could make a little tape recording, and I just thought it was a mad scientist laboratory. I was always hooked on knobs and dials. So recording studios were a fascination of mine before I ever got to set foot in one.”

“To this day, I have a really strong taste for Mariachi music.”

After spending a few years of the hippie era hitchhiking around the country, Geza returned to LA and started hitting the streets, going to recording studio after recording studio and asking if they needed any help. Finally, the manager of Artist Recording Studio on Cherokee Avenue (though it’s gone now) said that he could sleep on the floor and do odd jobs. From there, the story is fairly typical for producers and record engineers—the main engineer didn’t show up for a session and Geza was asked to do it instead.

“I think the musician’s name for that first session was Tony Perez,” Geza says. “It used to be cheaper to come to LA to record than it was in Mexico City, so a lot of Mexican bands would come up here with a case of J&B (whiskey). We’d get blasted, really blitzed, and record these old Mariachi standards. I cut my teeth on Mariachi, funk and disco. To this day, I have a really strong taste for Mariachi music.”

With that little bit of experience under his belt, Geza felt cocky and, as he had started hanging around an infamous LA punk club called the Masque, he began telling all of the bands that hung out there that he was a record producer. The Germs were the first band to bite.

“I was one of the original punks—there was maybe 40 of us at the very beginning,” he says. “The Masque started as a rehearsal hall and I helped them put in some PA equipment. They started doing shows, they built a small stage, and the Masque became like a hangout. I had started spreading the word that I was a record producer, something I had never actually done. I didn’t even know what a record producer was, to be honest with you. [Germs Singer] Darby Crash’s name was Bobby Pyn in those days. He tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘You’re a producer? Produce the Germs.’ I said, ‘Great, who’s putting the record out?’ He said, ‘Slash Magazine,’ and I was really excited about that because I knew that Slash was a kingpin of the scene at that time. That was the first serious Germs single, the first Geza X production, and also the first Slash Magazine record.”

That Germs single was the brutally brilliant Lexicon Devil EP, named after the leadoff track. People in the punk scene listened and, thanks to a national “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” unspoken arrangement between fanzines like Slash in California and Touch and Go in Michigan, word of the Germs spread fast. It was while in San Francisco with another LA punk band, the Screamers, that Geza made a connection that would change his life.

“Someone brought a girl in one day who used to be in a band called The Graces, which were an offshoot of the Go-Gos,” Geza says. “This was Meredith Brooks.”

“Things happened quickly in those days and, since all of the bands were tightly knit, we started going north to the Mabuhay Gardens, which was the big spot in San Francisco with all the punk bands,” he says. “We met these two guys named Jello Biafra and East Bay Ray. They were telling us about this band they were about to start called the Dead Kennedys. Not long afterwards, we went up there again and I got a chance to see the Dead Kennedys play. I remember thinking that I would practically cut off a nut to record this song, ‘Holiday in Cambodia.’ Just a few weeks later, Jello Biafra calls me. He says that they’re planning to record it and want me to produce it.”

There are many important songs under the punk umbrella, from the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog” to the Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop”; from the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK” to the Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks”. But the Dead Kennedys’ “Holiday in Cambodia” is right up there, thanks in no small part to the immense sound that Geza helped to generate. In fact, getting that sound was a trial in itself.

“It just sounds like a big, loud song,” Geza says. “But actually, the vocals on the chorus are quadrupled. That’s why they sound so humongous. On the verses, they’re single. On the pre-chorus, they’re doubled. It just builds so dramatically. In punk rock, it’s not supposed to sound produced but it was produced to death. We did it punk rock-style where we made it sound crude. That’s one of the reasons that song has really stood the test of time.”

With a solid reputation behind him, Geza opened a studio called City Lab in the mid 1980s with his then-girlfriend Josie Cotton, who had a hit with the single “Johnny are you Queer”. She had a house in the Hollywood Hills, and the pair converted the garage into a studio. Work was steady and then, in the mid 1990s, his life was changed again.

“Someone brought a girl in one day who used to be in a band called The Graces, which were an offshoot of the Go-Gos,” Geza says. “This was Meredith Brooks. She started playing guitar, and she played it like a maniac but a lot of her songs sounded dated. She had a lot of talent, so I told her to go back to square one and try to bang out a really modern song. She disappeared with a couple of months and then came back. She had done some co-writing with Christina Aguilera’s writer, Shelly Peiken. She came back with an acoustic guitar and strummed three chords and started singing, and my jaw dropped to my feet. It was like my entire arms turned to ice. She was playing the beginning verse of “Bitch.” The song was so good that I was flabbergasted. I said that we had to record it right there and then.”

That’s exactly what they did, and Geza says that they knew right away they had a hit on their hands. When Perry Watts-Russell from Capitol Records heard a rough mix of the song, he instantly agreed and signed Brooks to a contract on the spot.

“I still have an industry scar, but these stories are so typical. It’s not like I’m the first person that’s happened to.”

“People think it’s so hard to pick a hit song but no,” Geza says. “The public always gets it right. It’s ironic that you have all of these A&R people and record executives agonizing over this process, when you can just put it out to the public and just go, ‘Do you like this song?’ Nine times out of 10, everybody gets it. This is one of those moments where everybody knew it was a hit.”

“Bitch” and the accompanying Blurring the Edges album should have been the start of a long and illustrious career for Brooks, but commercial success has eluded her since. For Geza, the whole episode left its scars because, after he was done with “Bitch,” the album was taken away from him by the label and every other track was produced by David Ricketts.

“They finished the album, they redid all of the songs except for ‘Bitch,’ and the album went double-platinum,” Geza says. “I could have made a million dollars and instead I only made $100,000. It’s a little ugly, I still have an industry scar, but these stories are so typical. It’s not like I’m the first person that’s happened to. They ain’t gonna do it to me again though; I went indie again after that.”

With Geza and Cotton drifting apart as a couple but still working effectively as business partners, their next venture, soon after the Meredith Brooks adventure, was a new studio called Satellite Park.

“Josie had some money in her family and, after ‘Bitch,’ everybody was stoked on me and they were like, ‘Yeah, build a studio—here’s some money’,” Geza says. “She bought this big mansion on four acres in a gorgeous section of Malibu. We lived there, but we also ran it as a residential studio. I was able to build literally my dream studio in the hills and live there for 13 years. To our credit, we recorded mostly indie bands. We never really ran it as a big money maker. We treated the bands really well. They could make an album for $3000 at this plush resort. It was hard in a way because it was a labor of love. We had to pull three or four projects a month to be able to pay the bills but we did run it the way for about 13 years and it was really a lot of fun.”

Satellite Park closed in 2011 because, says Geza, of complications with the mortgage. By then though, Geza had decided that he wanted to work on some philanthropic projects after smoking 5-MeO-DMT and having what he describes as a spiritual experience. He connected with Cameron Melville and Jeff Parker who were just starting what they were calling the Philanthropic Center for the Arts. Geza renamed it The Vortex and was the first person to live there.

“The building was just a raw space at the time that since has been developed into live/work lofts, a coffee shop, and a space to put my studio,” he says. “Now, it’s a complete multimedia studio. I’ve got video editing gear, I’ve got two really good Protools setups, I do soundtracks for films and I also do disc mastering. Very little mixing and record production—I do a little bit of it but I’m not as interested in that. I help set up shows for the Vortex at the community center because it’s a whole multimedia theater.”

“I wanted to capture these people’s stories—not just the punk rock story, but what they did before, during and after, what they do today.”

And that’s where Geza X is today. He’s working on documentary movies at The Vortex, and he started a nonprofit called Hyperactivists that aims to preserve underground culture, mainly through film.

“I’ve always been about culture preservation,” he says. “Even when I was doing the punk rock records, I knew that if I don’t do them, nobody’s going to. So I’m about preserving underground culture. I’m fascinated by the sociological aspects of underground culture as it enters the mainstream and why that happens. I started with a series of films on punk rock because I had great access on all of that. I wanted to capture these people’s stories—not just the punk rock story, but what they did before, during and after, what they do today.”

Donations for the films are collected via a GoFundMe page, and Geza is quick to credit the people that he has working with him, including his wife Larva, a photo choreographer. He swears that it’s the people around him that are making things happen at The Vortex, and he has a point but he’s also being humble. Geza X might not be rich, but he’s always placed himself in and around interesting artistic endeavors. If his name has been attached to a project, it’s unlikely to be dull. Long may he continue.

If you would like to donate to The Vortex’s “Punk Rock Documentary” project, go to their GoFundMe page.