Bruce Lee’s daughter, Shannon, recently spoke out against Once Upon a Time in Hollywood for portraying her father as an arrogant caricature who is defeated by Brad Pitt’s stuntman character in a fantasy. Shannon Lee asserts, “they didn’t need to treat him in the way that white Hollywood did when he was alive.” This understatement only scratches the surface of the racist discrimination Bruce Lee faced both in his lifetime and in the depiction of his legacy—in which he is either relegated to sidekick characters (even in his own biopic), or to being passed over for starring roles in favor of white actors in yellowface. Hollywood is just the latest example of this treatment on the silver screen.

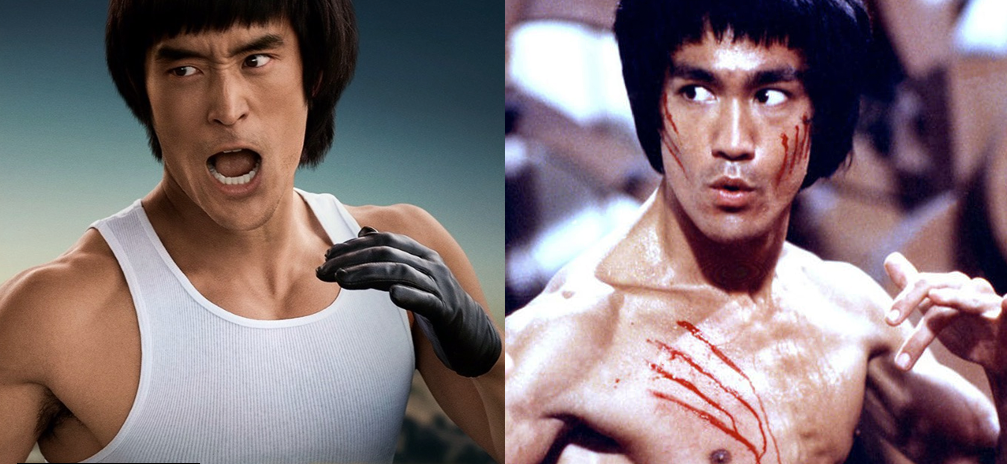

Mike Moh, the actor who plays Bruce Lee in Quentin Tarantino’s film, first made waves in the Asian-American community in 2012 when he created a since-deleted inspirational video dedicated to Bruce Lee using audio of the philosophical “Be Water, My Friend” speech from Bruce Lee: The Lost Interview. As a bonafide fan, Moh has since expressed ambivalence about his depiction of Lee in interviews. Even Brad Pitt noted feelings of conflict at the original premise that his character would categorically defeat Bruce Lee in the sequence.

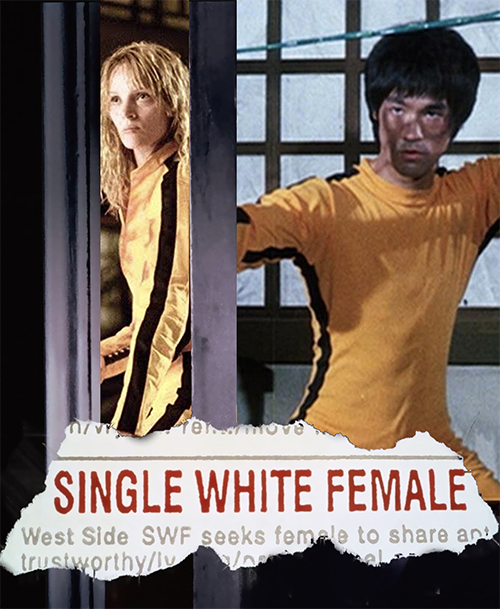

Real talk—Quentin Tarantino has been Single-White-Female-ing Bruce Lee with his films since at least Kill Bill: Vol. 1. Not only has there been mixed reactions to Uma Thurman’s The Bride character wearing Bruce Lee’s iconic yellow jumpsuit from Game of Death while murdering scores of Asian men, but Tarantino also made the loaded choice in casting David Carradine as the eponymous Bill. In fact, it was Carradine who beat Bruce Lee for the lead role in the show he created, Kung Fu. Where Carradine portrayed a martial arts master in yellowface. Although Mike Moh defended Tarantino’s reverence for Lee in his Birth. Movies. Death. interview, it’s clear that this “reverence” does not translate to practical respect for Lee’s legacy. Tarantino reportedly consulted the late Sharon Tate’s family about her depiction in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood but in telling contrast he failed to do so with Bruce Lee’s family.

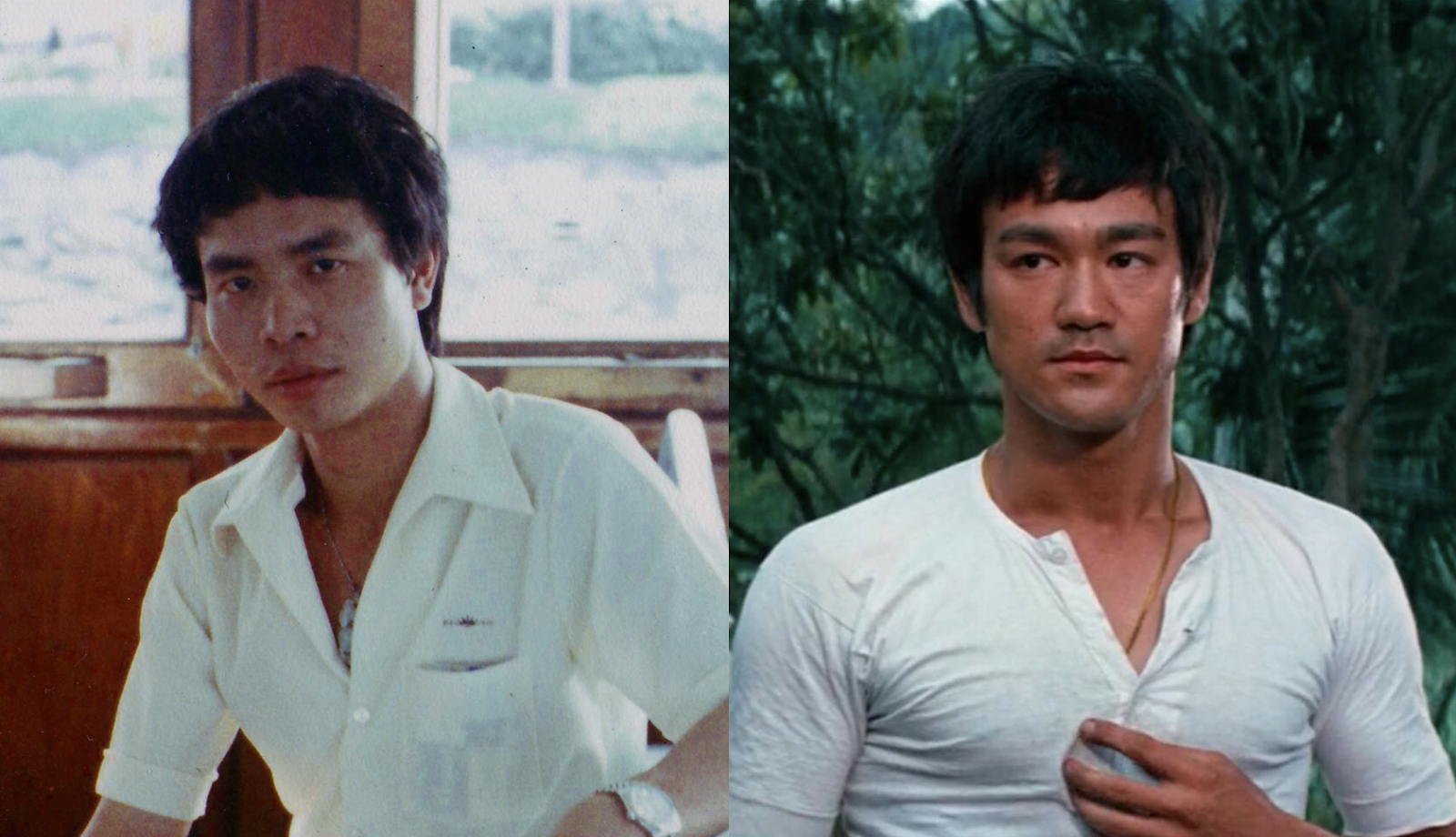

So why does all of this matter? As a Chinese-American woman, I grew up taunted by my classmates with Kung-Fu noises and derisively-accented broken English intended to “other” me. I also share a family name with Bruce Lee (romanized differently but the Chinese character and pronunciation are identical) so it wasn’t a stretch for bullies to make unflattering, alienating, and racist comparisons to him. While my family consistently held a high opinion of “Little Dragon Lee (李小龍)” as he was known in China, in America I became conditioned to disassociate myself with any part of this person who my bullies had weaponized against me—including my own family’s cultural and physical resemblance to him.

It wasn’t until well into adulthood that I unlearned this internalized racial bias and became open to seeing what an extraordinary person Bruce Lee actually was. I first became angry at myself for wanting to disown such a significant figure from my culture, then I became angry at my bullies for distorting one of the only Asian-American icons we had into something they could use to humiliate children of Asian descent. And with the newest reports of theatrical audiences laughing at the portrayal of Bruce Lee on screen, it’s become clear that this pattern of characterizing Lee’s distinctly Asian traits as being worthy of mockery shows no signs of stopping.

Over time, I’ve seen more and more Asian-Americans experience a similar trajectory to mine—this very same prodigal rejection and rediscovery of an icon that has been wielded by and against Asian diasporic culture as a double-edged sword. Asian-American journalists/bloggers Jeff Yang and Phil Yu even run a podcast entitled “They Call Us Bruce”, inspired by this phenomenon. Yang explains, “The name is both an homage to Bruce Lee, an iconic figure and pioneer for our Asian American community, and a reference to the 1982 movie They Call Me Bruce?, starring Korean-American comedian Johnny Yune—about an Asian American guy who gets mistaken for a martial arts master. There’s an irony that someone like Bruce has entered into culture both as an aspirational figure and the source of a stereotype, and we highlight the tension that exists in that dual imagery in our podcast.”

Asian-Americans have worked so hard to emotionally reclaim Bruce Lee, after having the icon used as a jeering effigy against us, that Tarantino’s portrayal of him carries an extra sting. Essentially, they took one of the few positive representations of our culture, twisted it into something that could be used to mock us until we rejected it, then proceeded to appropriate it into fictional white wish-fulfillment fantasies where they can then subjugate the very Asians that originated the culture.

It doesn’t just happen with martial arts. It happens across the entire spectrum of Asian culture; from our food, to our stories and characters, and even to the fetishization of Asian women as objects to be won in some sort of White Savior fantasy—which has been shown to have some truly dire consequences in the case of a white man who targeted and murdered three Asian men just earlier this year in New York in the interest of “defending” Chinese women.

In recent years, there has been a disturbing proliferation of this trope where white protagonists are portrayed as being “better at being Asian than Asians” by either defeating Asian masters or just cutting down dozens of Asian men as a show of their might. The latter is so common, even in media that’s stirred up less controversy—

like Netflix’s Daredevil, Deadpool 2, and Hawkeye’s Japan scenes in Avengers: Endgame—that it’s almost as if Asian men being presented as some faceless monolithic entity has dehumanized them to the realms of disposable and

robotic NPCs.

Representation of a culture and of its icons is important because it has real-world ramifications on members of that culture and how others treat them. This dehumanization of Asians as a source of competition to subdue has an enduring impact in the form of “Yellow Peril”, which has contributed to a long history of anti-Asian violence and legislation. With Asian-American representation taking huge strides in cinema in the past few years with entries like Crazy Rich Asians, Always Be My Maybe, and The Farewell; one can only hope that a setback like Bruce Lee’s portrayal in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is more of a swan song of a dying era than an omen of things to come.

Alice Meichi Li (李美姿) is a Chinese-American illustrator and writer who’s originally from Detroit and currently lives and works in New York City. Follow her @alicemeichi.