As we sat in a hotel in New York on a rain-soaked Wednesday my colleague, T. J. Callahan, turned to me and said, “If more people could talk to filmmakers, we’d like more films.” She was speaking to the depth of understanding that dawns when you hear the genesis of a story, where it finds its mirrors in other art, and what in the work is meant to heal.

Pinocchio is easy to adore in this iteration. It is a classic reshaped into a storybook in medias res, transforming the parable into something mythic but with teeth sharp enough to break our hardened shells. Directors Guillermo del Toro and Mark Gustafson, alongside lead animator Brian Leif Hansen, have created a pocket universe, one seen through the light of a keyhole, leaving us to wish for keys to get inside.

—

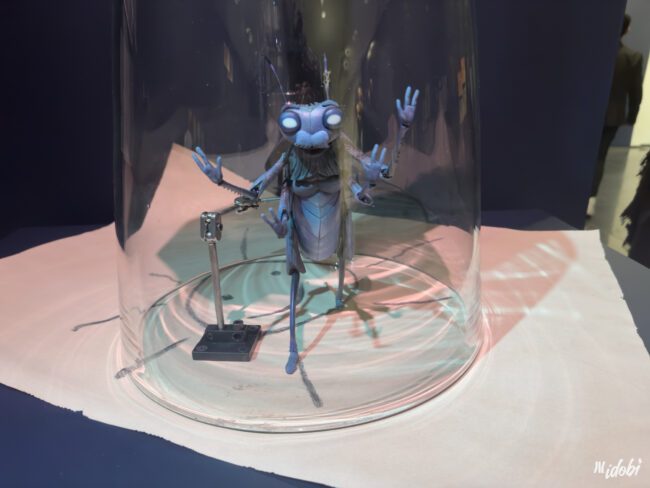

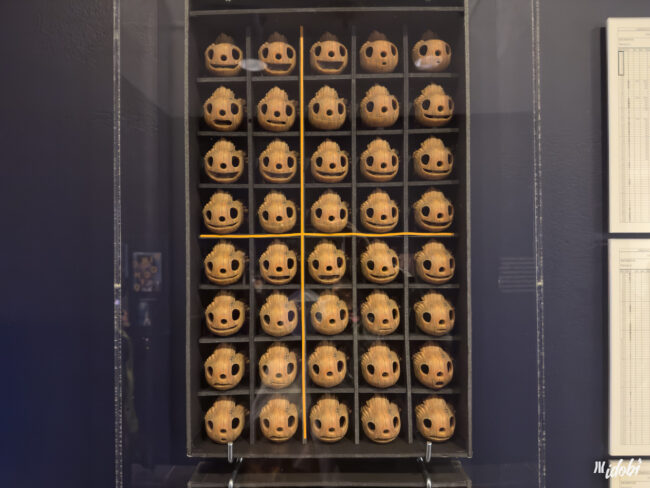

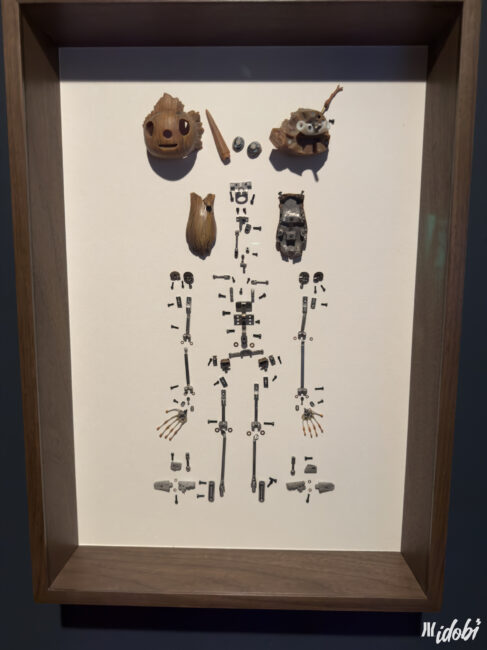

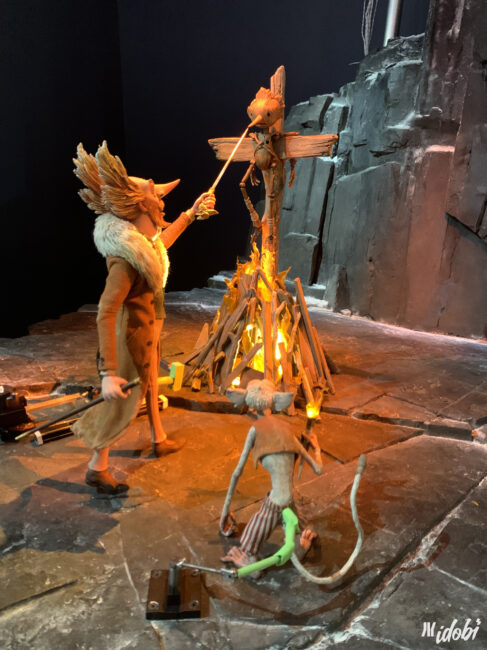

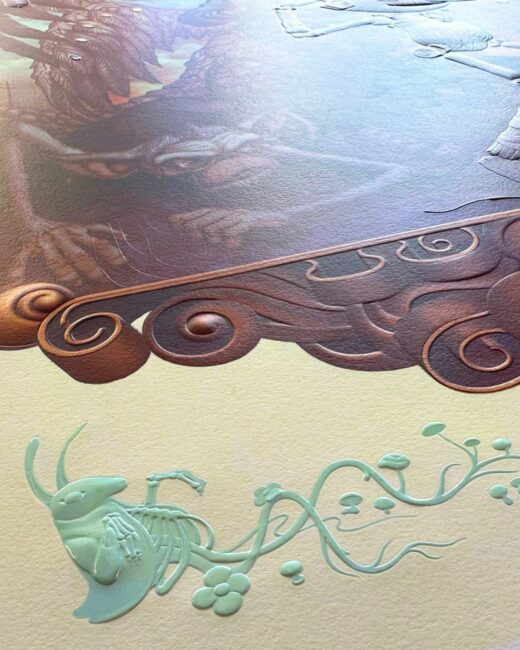

Part of that unlocking can be found at MoMA when you enter the Crafting Pinocchio Exhibit. Go as soon as you can. It follows the complete making of this film but also Guillermo’s career. There are puppets and art and sets and a poster created by my favorite artist James Jean. Luckily, we were allowed to gather around Brian for a bit of insider trading. He shared the layers of plastic (yup) and digital animation that went into creating an ocean that is tumultuous and threatening and fathoms deep but also indistinguishable from stop motion. And he shared that every 4 seconds of the film took a week to make—or as the directors like to summarize, “We shot for a thousand days.”

Creativity Is An Act of Catharsis

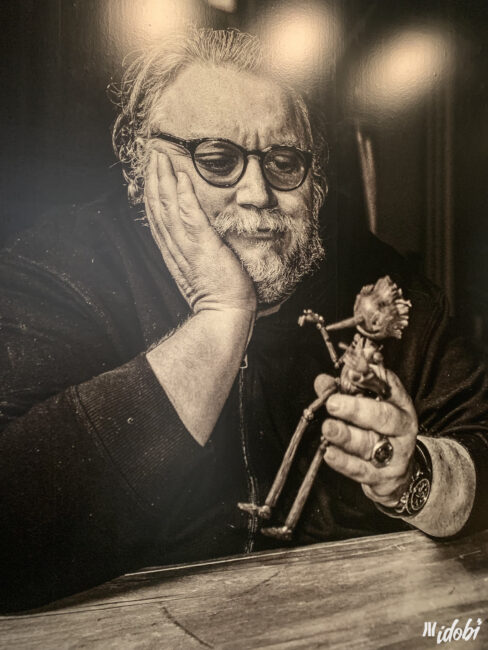

T.J. is right. What was endearing before we spoke with the creatives became illuminating after. Not only in the process but the emotional wounds it seeks to heal or at least to ameliorate. Mark says, “…really, if you look at the film, it’s kind of Geppetto’s story more than it is even Pinocchio’s story because he’s the one who has to — it’s not like he finds love, he recognizes it eventually. And that’s the arc that he’s on. He just doesn’t see it, to begin with.” Guillermo follows up with, “You have Pinocchio learning to be a boy in all the other stories, and here is Geppetto learning to be a father. And that is far more valuable, I think.”

—

This revelation later leads to a “heart-wide-open” moment when Guillermo shares, “…certain movies you know are gonna be a drop of healing for everybody and yourself. I think that this movie not happening for more than a decade and then happening, it happened at the right time.” He searches for the words and continues, “I think on a personal level, I was able to deal with how I was failed too as a son and how to live with that imperfection and see my father as a human being, as a guy that happened to be my father, but he couldn’t fathom that. No one can. The father is a figure that surpasses biology and physicality. It’s a shadow of gigantic proportions. And my failings as a father and the passing of my father. So it’s a healing movie for me.” With that, he is overcome and Mark pats his back—perhaps it is also a film about brotherhood. Pinocchio, Candlewick, Spazzatura, and Cricket would agree.

—

Extending Into the Sky

Guillermo spoke more about how he became the storyteller he is, “When I was a kid, there was only one model for filmmakers in Mexico. The language of liberation was used to oppress. [They said], ‘You have to make movies about your reality exactly. And you have to portray only this type of story.’ And I disobeyed. I said I wanna do Flights of Fantasy that bring us back to reality and explain some truths. I wanna make movies with animated characters and giant robots and gothic romances because: My roots are in Mexico, but my branches extend to the sky.”

“We don’t wanna see “motion.” We wanna see “emotion.”

And yet if GDT’s Pinocchio is about anything it is awakenings—the idea of rising to meet yourself or refusing to wake and never knowing flight. This concept, for me, infuses every candlelit moment you spend inside this pocket universe. It is in Pinocchio’s first rising, when he understands nothing but an unintended and yet destructive curiosity (and he sings my favorite song of the film, “Everything Is New to Me”). Our Wooden Boy must awaken again with each fatal mistake he makes. Geppetto must also rise in revolution after revolution (all puns intended) to meet the challenges and emotional detonations of fatherhood. And Cricket (Sebastian J. to be exact), who was searching all along, must wake to see that what we seek is sometimes only a signpost pointing towards what will fulfill us. The emotional fabric enwrapping this film, reveals our hearts die many deaths but its resurrection is a matter of the depths of our souls.

—

Guillermo says the same, “We don’t wanna see ‘motion.’ We wanna see ‘emotion.’” He and Mark sought a humanity and tangibility, adding days to the schedule to show the characters in “failed acts” (tripping, reaching but missing, expressions of misunderstanding). “[puppets] are avatars that are almost superhuman,” Guillermo says. “We empty ourselves into them. It’s an act of magic that only animation has. And animation, that’s why it is a goddamn art form. And we need to respect it like that because it’s the only one that gives us that experience. It’s an act of magic.”

What more can I say? Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio is an act of sorcery, an enchantment that renews itself each time you look through that wondrous keyhole. Where the only strings attached are the ones that play the heart.

“You sing a single song in your lifetime, but if you do it right,

in a state, somewhat, of grace, it becomes everybody’s song.” –GDT

—

For a deeper dive behind the scenes, stream GUILLERMO DEL TORO’S PINOCCHIO: HANDCARVED CINEMA, available on Netflix now.

—